Possible vocabulary words are everywhere. We are bombarded with endless possibilities of words to teach our students. The words come from mentor texts, independent novels, word lists, district mandated words, academic words, reading programs, vocabulary programs…the list goes on and teachers feel the pressure.

As a Common Core state (per se), NJ teachers are working their hardest to meet the increased expectations of national standards. The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) put heavy emphasis on vocabulary, by making it an anchor standard at all levels K-12.

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standard for Language

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.L.6

Acquire and use accurately a range of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases sufficient for reading, writing, speaking, and listening at the college and career readiness level; demonstrate independence in gathering vocabulary knowledge when encountering an unknown term important to comprehension or expression.

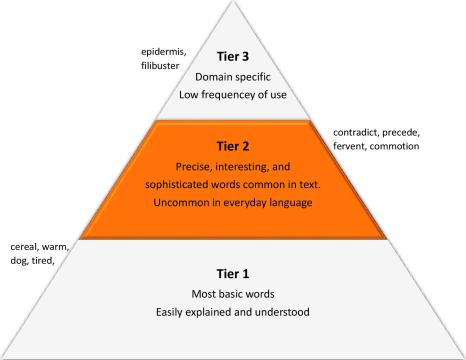

I do not disagree with the CCSS attention toward vocabulary. I understand that a greater vocabulary makes more complex texts accessible to students and, in turn, increases their reading levels. And we are all familiar with the correlation between reading, vocabulary, and test scores- made clear with this popular info-graphic.

But for all its gusto, what the CCSS does not do, is tell us what the appropriate academic and domain-specific words are for each grade level. It is left to the discretion of teachers and/or curriculum planners to determine words appropriate for individual classes or grades, and this is a daunting task when faced with the wide variety of sources out there. In all the hustle and bustle of daily classroom instruction, it is this sort of huge task that can easily get put to the wayside. So, this post offers suggestions to the first burning question about vocabulary instruction:

“Where do I get the vocabulary words to teach my students?”

A firm belief I have is that prescribed word lists or programs are not the answer.

Keeping the belief of the workshop model in mind, vocabulary words taught in the classroom should be as authentic as possible. Students need to see these words coming from themselves and their experiences. The relationship between ownership, motivation, and engagement is not a secret. When students are invested in the words they are learning, vocabulary instruction will be more meaningful and you will have a very clear answer to the “Why are we learning this?” question.

My suggestion is to pull words from the following three places.

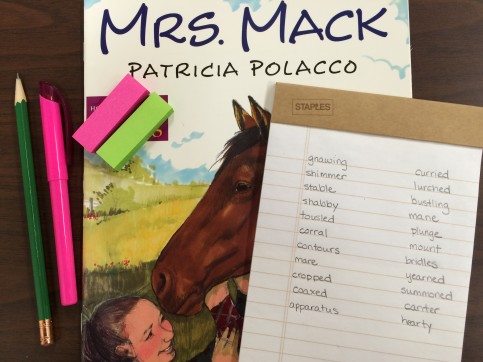

1. Your current mentor text

These would be completely teacher-selected words chosen from the mentor text that you are currently using to support your teaching. These are the words that you would have the most control over.

2. Student’s independent reading novels

Since choice is a large part of the workshop model, it is important that students have the opportunity to provide input on the words they want to learn. By allowing students to choose the words they will learn, you are tapping into their sense of ownership.

Greg Feezell, in his article “Robust Vocabulary Instruction in a Readers’ Workshop” featured in The Reading Teacher (Vol.66, Issue 3, 2012) suggests encouraging (as opposed to requiring) students to submit words to a “Word Box”. These might be words students find interesting or words that they wish to understand better. They can be chosen from texts read during independent reading time, at home, or in other subjects. Using a submission process allows you, as the teacher, to have final veto power over which words are chosen for instruction- a valuable aspect of this system.

3. Student’s writing

Have you ever noticed how when you spotlight a single student, the level of the entire class is lifted? We do this for good behavior. “Johnny, I like how you are sitting up in your chair, ready to learn.” Suddenly, the whole class grows taller as they work to emulate Johnny and seek our approval and praise. Kids want to be their best selves, but sometimes they need to be reminded of just how great they can be. This method works to tap into that phenomena.

While working with Teachers College Reading and Writing staff developer, Emily Strang-Campbell, in some of our district’s 4th-8th grade classrooms, a technique that spotlighted student vocabulary use in their writing was introduced. During independent writing time, when students were writing fast and furious, Emily walked the room to note students that had used strong vocabulary in their writing. During the mid-workshop interruption she gave selected students a shout-out compliment and started a list of their words on the board. As the students went back to work, Emily suggested that everyone push themselves and try to use one of the strong words listed or any other strong word they know in their writing during the final stretch of independent writing time that day. You would have been amazed with what the students accomplished! The power of a compliment.

We can tap into this and choose vocabulary words for instruction from the words that were spotlighted from student writing. Imagine the power these words would have for students, coming from the pens of their own classmates!

These sources give you valuable, authentic vocabulary words that students will be invested in. The next step of the process is choosing which specific words to teach from these sources. My second post of this series will offer suggestions to do just that!

Are there are any other authentic places where you pull vocabulary words from for instruction? I would love to hear from you!

Let’s keep the conversation going-

Lindsay

Years and years ago, before I had been bitten by the writing workshop bug, I became obsessed with vocabulary instruction. My school used a series of vocabulary workbooks at each grade level, and I had witnessed how that approach didn’t worked. Not for real. Not for the long term. Some students would dutifully memorize the words, earn a high score on the quiz, and forthrightly forget most of what they had learned. Many of my students would even bother — they would sort of study the words, sort of learn some of them, earn a low quiz grade, and move on with their day.

Years and years ago, before I had been bitten by the writing workshop bug, I became obsessed with vocabulary instruction. My school used a series of vocabulary workbooks at each grade level, and I had witnessed how that approach didn’t worked. Not for real. Not for the long term. Some students would dutifully memorize the words, earn a high score on the quiz, and forthrightly forget most of what they had learned. Many of my students would even bother — they would sort of study the words, sort of learn some of them, earn a low quiz grade, and move on with their day.